You Have to Live the Life You Sing About

“If you can't speak out against this kind of thing, a crime that's so unjust,

Your eyes are filled with dead men's dirt, your mind is filled with dust.”

-Bob Dylan, “The Death of Emmett Till”

Black History Month 2003

People “who made a difference” can be found by simply opening a book of American history to any page. After a long struggle, historians today grant what should have always been obvious: African Americans are an important part of this group. They have contributed mightily to every aspect of American life. These women and men were “great” by any measure historians might use.

What is our nation’s music without the genius of Louis Armstrong or our literature if Zora Neale Hurston’s writings should be found missing? A taproot of investigative journalism is in the reports of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and our economic-political thought (and so much else) was enriched beyond measure by the works of W. E. B. Du Bois. These few are only representative of a host of justly famous African Americans. They helped to make America what it is today and what it will be tomorrow.

Greatness, however, is too often narrowly defined. Each February Black History Month serves to remind us that the past is also the story of a kind of greatness that can elude even careful historians. This absent story is that of the greatness of individuals doing what is right and often courageous, whether it be in the flash of one day or in dedication lasting over many decades. These are people who act in ways that change minds, change lives and even serve to play a role in profoundly changing history.

Historians, pressed by space limitations or hemmed in by standard assumptions on how to weight the actions and impact of individuals in the public arena, generally fail to find ways to weave these “invisible” heroes into the historical record. Black History Month is a good time to briefly recognize one of these unacknowledged heroes.

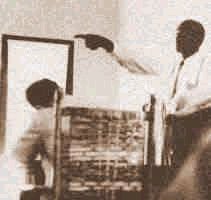

“Thar he,” were the words of Mose Wright in a courtroom in Mississippi in September of 1958.

Wright was testifying in the trial of two white men accused of removing his nephew Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old boy, from his house and brutally beating and killing the boy. The indictment read that young Emmett was killed by a shot through his ear. Till’s body was disposed of by tying a heavy cotton-gin fan around his neck with barbwire and tumbling him down a steep bank into the Talahatchie River.

Emmett Till was from Chicago. He was visiting the original home of his mother for the summer. It was his first trip to Mississippi, called by some “The Hospitality State.”

Emmett Till was from Chicago. He was visiting the original home of his mother for the summer. It was his first trip to Mississippi, called by some “The Hospitality State.”This gruesome murder took place in the summer of 1955. At a trial in 1958 Mose Wright put his life in danger and agreed to be a witness for the state. He was placed under oath. But more important than the oath he pledged on the “Negro” Bible (even the book of books was segregated in 1950s Mississippi), was a solemn recognition and choice coming from deep inside of Mose Wright. This slight man, five foot three inches tall, 64 years old, a sharecropper most of his life, decided for himself that it was time.

It was time to no longer turn away from the crimes of racism. It was time for personal courage to speak truth to power and intimidation. It was time to say to himself and then say to the world that the blood shed in support of slavery and the blood shed in support of segregation would not close up the mouth of Mose Wright. It was time to desert the false safety of silence. It was time to speak.

“Thar he.”

With those words, Mose Wright pointed out the two defendants who had entered his house and dragged Emmett Till into the night.

Here is how Murray Kempton, who attended the trial and was one of the finest journalists of that era, described the significance of his act:

“If it had not been for him, we would not have had this trial. It will be a miracle if he wins his case; yet it is a kind of miracle that, all on account of Mose Wright, the State of Mississippi is earnestly striving here in this courtroom to convict two white men for murdering a Negro boy so obscure that they do not appear to have even known his name.”

Striving as they might, there would be no miracles. The State of Mississippi failed to deliver justice in this case. After deliberating all of an hour and ten minutes, the all white male jury found the defendants not guilty. A few months later Look magazine purchased the former defendants story. Now “free” men, they admitted to murdering Emmett Till.

During Black History Month, we all, every one of us, can be moved by lives such as Mose Wright’s. Here is an individual who acted with conviction while surrounded by hostility and without the expectation of fame and recognition.

Strange isn’t it how some people continue to be blind to the inspirational benefits that fill the story of African Americans in our nation’s history? Mose Wright’s life moment offers something everyone can aspire to achieve.

If they have the courage to do so.

If they will remember Mose Wright.