Unwitnessed Courage

I helped win sweet victories,

With my plow and hoe,

Now, I want you to tell me, brother,

What you gonna do 'bout the old Jim Crow?

Now, if you is white,

You's alright,

If you's brown,

Stick around,

But if you's black,

Hmm, hmm, brother,

Get back, get back, get back.

–Bill Broonzy, “Black, Brown and White” (1949)

Sixty years and counting. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down its Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision. It was a ringing 9-0 opinion stating that segregated schools were inherently unequal. Unfortunately this bold moral ruling was followed by a slippery “with all deliberate speed” remedy. Problems remain.

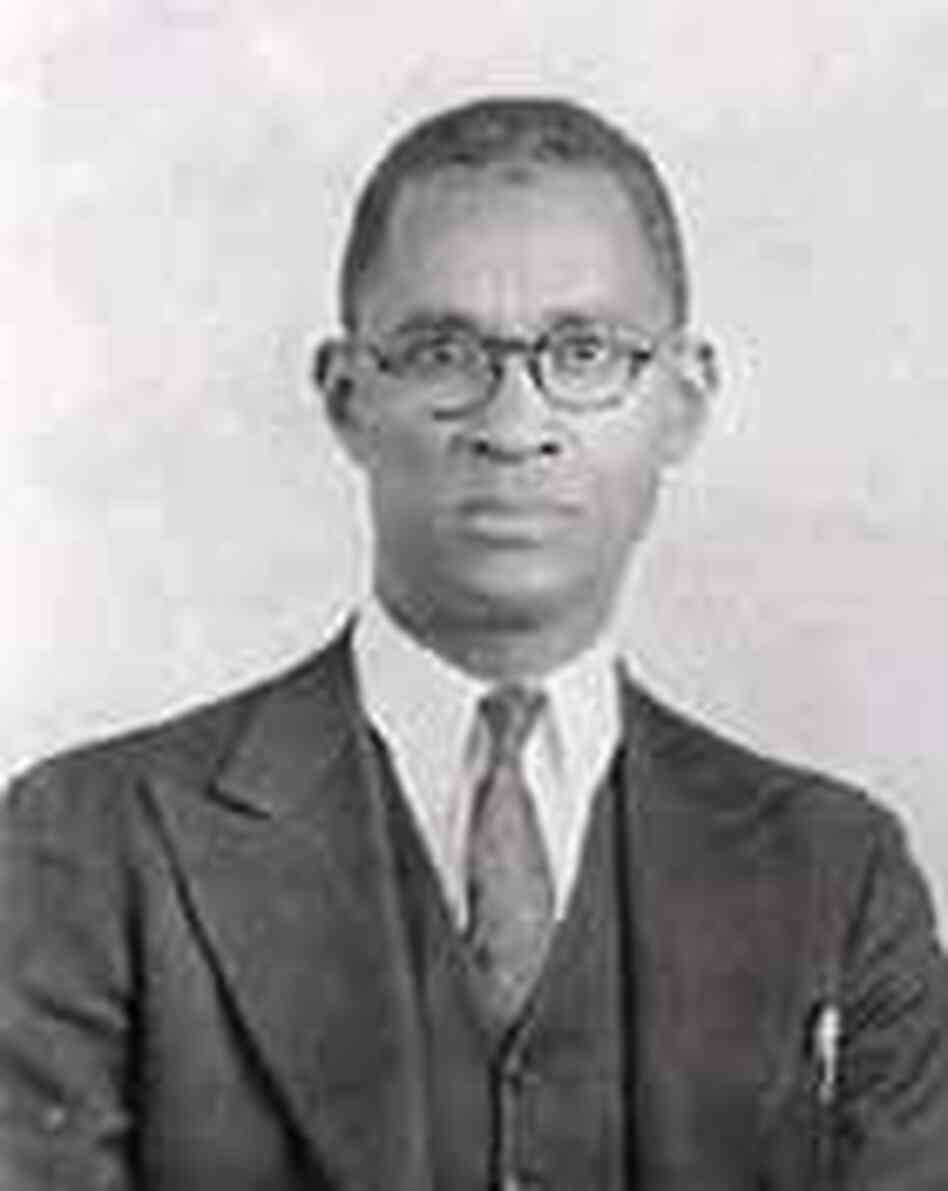

As academics and pundits review the half-century since that decision electrified the nation, it’s worthwhile to remember the unwitnessed courage it took to bring the historic Brown v. Board case to court. The story of that struggle is about more than judges in robes and lawyers in their best suits. It’s the story of people like Joseph Albert DeLaine.

In 1896, the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson gave its blessing to the “separate but equal” doctrine. This decision legalized racial segregation. It also stamped white supremacist views with the implicit approval of the highest court in the land.

Dark habits of the heart hardened; thinking ossified; change seemed impossible. A pitiless rain of inequities and indignities fell on African Americans everywhere. Segregation pressed down on blacks from the cradle to the grave. It pressed down on J. A. DeLaine and the black citizens of Clarendon County, South Carolina.

DeLaine was born in Clarendon County in 1898, just two years after the Plessy ruling. Fifty years into his life, if you were black and lived in this county, the odds were strong that you were a farmer who raised cotton as a tenant, that you were in debt, and that your family lived from crop to crop on credit. Fully 3000 black households out of a total of 4500 subsisted on an annual income of less than $1000. In all of Clarendon County, only 280 of the black households managed an income of $2000 in a good year.

White supremacy and indifferent selfishness undermined education, America’s traditional ladder to self- and community improvement. In 1949-50, Clarendon County spent $43 on each of the 6,531 black children in its schools; the 2,375 white students were funded to the tune of $179 each. The black children’s school year was shorter and their teachers were paid less. African American school buildings and equipment were valued at $194,575, the white’s at $673,850. In the late 1930s, a survey showed that of blacks over ten years of age, 35 percent were illiterate.

Such were the wages of “separate but equal.”

Would it be surprising if hope for change withered in this corner of South Carolina while fear and apathy thrived? Can you preach and teach without hope?

Joseph Albert DeLaine was a preacher and teacher in Clarendon County. Mattie Belton was his wife and she was also a teacher. Sometime, somehow, during or right after World War II, the Reverend J. A. DeLaine decided that justice and dignity in the here and now was work worth pursuing.

In 1947, J. A. DeLaine started to listen ever more intently to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The NAACP strategy at the time was to go to court to legally require equal expenditures on black and white schools and students. A plaintiff of good character and a great deal of courage was needed. DeLaine was the natural leader in the community and he took on the daunting job of finding such a plaintiff.

Levi Pearson was the man DeLaine found to take on this risky role. To get to school in the rainy season, Mr. Pearson’s children sometimes had to row a boat across a flood plain. Wet or dry, they had to walk nine miles to get to their segregated high school. Whites splashed through or rolled along dusty roads in county supported busses on their way to their schools.

In June 1948, the Pearson case was dismissed on a technicality. Over a year’s time, Levi Pearson paid the price of his courage. He nearly lost his farm when he was denied the usual bridge loan by his white owned bank, he could not get whites to haul lumber he needed to sell, and the white farmer he always relied on in the past refused to harvest his grain crop. The crop rotted in Mr. Pearson’s fields.

But somehow the courage of J. A. DeLaine and more and more of the African Americans of Clarendon County did not rot like the oats and wheat in Levi Pearson’s fields.

Thurgood Marshall, the top man in the legal arm of the NAACP and a future Justice of the Supreme Court, came to Columbia, South Carolina, in March 1949. He met with J. A. DeLaine and a small group of Clarendon County blacks. Marshall was straightforward. Not one, but fully twenty plaintiffs were needed in order to directly attack segregation in public schools, the legal heart of racism.

DeLaine served as the leader in the delicate and dangerous task of finding willing paintiffs. All of black Clarendon County knew what had happened to Levi Pearson. But somehow DeLaine managed to teach and preach his way to signing on those twenty brave plaintiffs. He had the twenty by November of 1949.

When this case went to court in 1951 it was titled, “Briggs v. Elliott,” taking the first of the names on the list of twenty petitioners, Harry and Eliza Briggs. Harry Briggs was a Navy veteran who had worked as a gas station attendant in Summerton, South Carolina, for fourteen years. On Christmas day 1949 Mr. Harry Briggs’s employer fired him. The firing came with this Christmas message: “Harry, I want me a boy . . . .”

Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 brought together five school desegregation cases under one title. The Briggs case was one of these five. In “Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South,” John Egerton writes: “I find myself wishing that the title case had been Briggs v. Elliott [rather than Brown v. Board of Education] . . . or better yet, something like DeLaine v. Clarendon County.”

Richard Kluger relates Joseph Albert DeLaine’s background and contributions to the Brown v. Board decision in his magisterial history “Simple Justice.” He also sums up what this unsung hero received for his efforts.

Here’s that summing up in stark terms. Imagining what life was like for J. A. DeLaine and his family as they went through these nightmare times can never be summed up.

Joseph Albert DeLaine and Mattie Belton were both fired from their teaching jobs. Joseph Albert DeLaine was frequently threatened with bodily harm. Joseph Albert DeLaine’s house was torched, left in a heap of ashes, while the local fire department stood and watched. Joseph Albert DeLaine reported to the police that he had been fired on with shotguns. The police never responded to his calls. The Reverend Joseph Albert DeLaine fled the state of South Carolina when he was falsely charged with felonious assault and his church was burned to the ground. Joseph Albert DeLaine never returned to Clarendon County or to South Carolina.

Kluger concludes: “All this happened because he was black and brave. And because others followed when he decided the time had come to lead.”

Outside of his local community, the bright flash of DeLaine’s heroic life was missed by most. When mentioned today, his sacrifice and success are abbreviated and shadowed. His unwitnessed courage deserves better.

Joseph Albert DeLaine, Harry and Eliza Briggs, and Levi Pearson were honored with the award of a Congressional Gold Medal on September 8, 2004 for their part in the long struggle to desegregate the public schools of the United States of America.