The “Nobody Is Us” Memoir

[gary daily col. 25 July 14, 2002]

I'm Nobody! Who are you?

Are you--Nobody--too?

--Emily Dickinson

St. Augustine and Sammy Davis, Jr., Ulysses S. Grant and Ann Heche, they all sat down and decided history and the world deserved to have their life stories at hand. The personal narratives of the powerful, the rich, and the celebrated have always been a magnet for readers. Some serve us well while others are as edifying as The Jerry Springer Show.

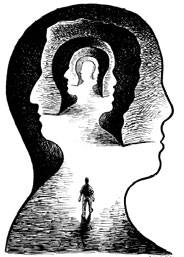

But what do you make of memoirs of “nobodies”? Frank McCourt and Mary Karr kicked off this spike in the market for books emphasizing the gritty details of lives not yet famous. And the list grows monthly. I’ll label these the “Nobody Is Us” memoir. What’s this all about? Who can be certain, but even the casual reader of this fare can spot some common themes explaining the interest and readership they garner.

“As the twig is bent the tree’s inclined,” goes the old saw. The truth of this bit of folk wisdom is radically ratcheted up in these books. Childhood is remembered as one part dark family life and one part cloudy landscape. Mom and Pop turn out to be the damaged clones of “Martha” and “George” freshly escaped from Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf.” And the home turf is about as far from Mr. Rogers' neighborhood as you can get. Whether living hard in a slum or a trailer park, living light in a comatose suburb, or living fat in a glitzy urban high rise, the child’s community always carries the zip code of a circle from Dante’s “Inferno.”

Here, in the green turned gray childhood years, twigs are not so much “bent” by heredity and environment as they are psychologically and sociologically gouged and bruised. These scars on the memory remain prominent, displayed in disfigured growth rings far into the future.

Next up, it’s welcome to adolescence. These are the years no responsible “Nobody Is Us” memoirist can ignore or quietly pass over. How could they? Barring participation in one of the recurring wars obligingly created by our leaders, what else represents a “peak experience” in young lives? Starting at age thirteen (twelve, if MTV was available to them), teens storm about in a haze of hormones, idealism, need, and loneliness. This is the stuff that sells books. Readers become nostalgic voyeurs to the memoir’s nostalgic exhibitionism.

“Nobody Is Us” memoirs catch the wave of adolescence and work it into a frantic frothing frenzy. Who is not familiar with the angst-ridden and pimple-faced teenager negotiating the unfairness, ambiguous fullness, and confusions of life? Needless to say they are severely overmatched. The manic-depressive elements of what constitutes the “youth culture” of the day are explored in sweaty detail. If the driver’s license was obtained in the fifties up into the mid-sixties, we read of “first time” carnal initiations, alcoholic adventures, and what was hip and meaningful in the pop music of the moment. The late sixties to early eighties (Yes, twenty-somethings are writing their memoirs!) are more direct, it’s sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll time, baby!

These not-quite-coming-of-age life dramas resonate with readers. They depict a period in lives profoundly and indelibly, if not always accurately, inscribed in memory. When we tune the radio to a station with a “Classics” format, we are involuntarily transported back into those years. A singer or song recalls the exquisite and the excruciating with perfect emotional pitch. That’s our music we say; it’s the soundtrack to our lives.

When relating the span in life from 25 to 45 (recognizing that every generation has its late-bloomers, its delayed conversions), these memoirs reach for redemption. The scourges of childhood are healed and the sins of adolescence are cleansed.

But there are always final hurdles to be vaulted. Here we may meet the baggage of bad marriages and worse divorces, a searching for love in all the wrong places, the failure to find satisfying work or ditch work that does not satisfy, the requirement of dealing with friendships lost, betrayed, and thinned out. In the most didactic of these memoirs, this is all “necessary work” if one is to be “happy” or “secure” or “complete” or to finally “love oneself.”

It’s a satisfying miracle to most readers when the “Nobody Is Us” memoir ends on one of these notes of “transformation.” As William Dean Howells put it many years before Hollywood cast it in celluloid concrete, “what the American public always wants is a tragedy with a happy ending.” Lives fated for ruin, ignominy and worse manage to right themselves through love, religion, or rehab. Surprisingly, luck and pluck, the good old nineteenth century deus ex machina, are only rarely called forth to clear away the psychological/historical underbrush hiding the yellow brick road to serenity and self-actualization.

Often floundering on sensational anecdote, or pushed along by strained coincidence, these memoirs can read like the script of a spiritless infomercial. And while it may be true that “everyone has a story to tell,” claims of authenticity cannot substitute for artful prose. But when they do succeed, when readers take away understanding not lessons, the personal memoir can be about more than Nobody, even about more than Us.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home